COP27 ended on a bittersweet note, with some achievements but mainly with growing frustration. For once, food and agriculture were given a more central place in the discussions. That’s good news, as only 3% of public finance directed to climate change goes to food. However, this creates intense debates that I feel will only get stronger in the years to come.

First, let’s rewind a bit to have a broad overview of why acting on agriculture and food is critical if we want to achieve our goal of limiting climate change.

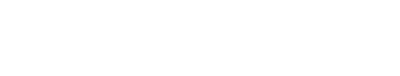

As you can see from the graphs below, food is responsible for 26% of global emissions (estimates vary up to a third). Animal products are responsible for a large share of it, directly and indirectly (land pasture). However, many other components of our diet also have a significant impact. Coffee and chocolate have a considerable impact, balanced by the small amounts we eat (Americans eat 100kg of meat yearly and “only” 5kg of chocolate).

It should be noted that there are many controversies around this data, notably on the impact of animal land use. It is hard to estimate the impact of a global food system made up of very different components (how cattle is raised in countries such as the UK and Brazil varies widely).

Then, what should we do about it? If assessing the situation is complicated, acting on agriculture and food is an even more delicate subject as people have very different thoughts about it. We could say that there are three “schools” or ways to look at the problem:

1 – Team “technology will save the day”.

This is where most solutions developed by FoodTech startups can be found:

- Replacing animal proteins with equivalents, either plant-based or coming from bioreactors (through precision fermentation or cellular agriculture). These are moving fast, with new pilot facilities announced almost every week. Alternatives to essential animal products are on the verge of reaching a wider distribution (even if scaling remains challenging).

- Replacing other “problematic” products, such as cooking oils, coffee and chocolate, with alternatives

- reducing food waste by digitizing the value chain

- replacing plastic with new synthetic polymers

- reducing the impact of farming by using new crops and sensors and developing more energy and input-efficient (indoor) farms.

With these technologies, we can imagine a drastically different future with far less of our land devoted to food (up to 40% less), no animals used for our food, and lots of indoor farms. If public money is slowly moving there (more and more projects are being supported by the EU, the US and some other countries), entrepreneurs are heavily funded (more than $5B went to alternative proteins last year) by private investors, which sees there a way to disrupt food as we know it.

2 – Team “regenerative & adaptation”.

This is where you will find many people whom the technologies mentioned above and radical changes imply are unpalatable. They defend the idea that by adapting our agricultural practices, we could significantly impact the food system’s impact on climate.

Beyond, a (large) subgroup could be called “team tradition” and is made of people who see the development of new food technologies as an attempt to change their way of life without their consent. The talk about lab-grown meat has often been frightening, and the activist behaviour of some startups may radicalize people against them (for example, should a startup do this?).

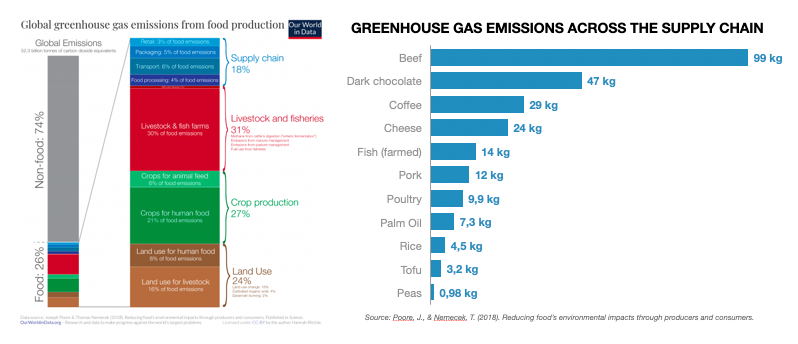

3 – Team “business”, which doesn’t focus on climate change’s negative impact but looks at the opportunities it is creating. They know they shouldn’t talk about it, but the options and their consequences are huge. It’s not just about avocados (a tropical fruit) being grown in Sicily. Just look at the map below and consider the geopolitical and economic impact of the yield variations related to climate change.

Coming back to this report which shows that only 3% of the climate-related public funding is going to agriculture and food, we understand how funding change in agriculture and food can be complicated. Even beyond choosing a path, it is extremely sensitive to have a public policy about what people should eat (when it is not for their health but for the environment). However, this should be something other than a debate of experts but something much more discussed openly. No comprehensive solution will come from a single voice, or we will keep discussing missed targets.