Recently, a significant number of startups have had troubles. Some survived the hardships, but many just went bust and filed for bankruptcy. Let’s look, with examples, at the five signs of distress in agrifood startups.

1 – Layoffs

Many tech companies have had layoffs over the past couple of years. This is not only observed in startups but also in large tech companies such as Microsoft or Meta. For startups, these layoffs are due to many factors, including the end of cheap money (and inflation), lower-than-expected growth, and a switch of focus. However, for most startups, this happens without the existence of a highly profitable core business activity.

Layoffs are generally the first externally visible sign of distress. It shows that the company can no longer convince investors to pour money into sustaining its initially planned growth trajectory announced (in terms of locations it wants to be active or in terms of projects it is developing). It is also simply a sign that revenue expectations (without mentioning profit) are unmet.

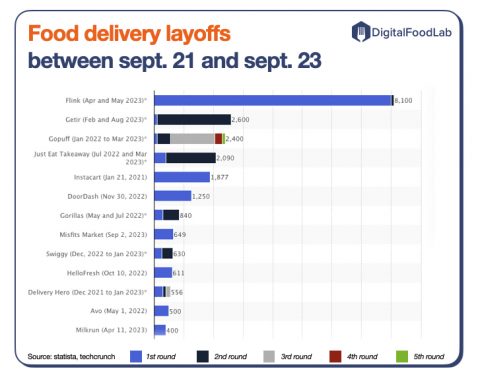

Nowhere is this more visible than for food delivery startups. As shown in the above graph (more details here, tens of thousands of people have been laid off in two years.

Also, as you can see, around half of the companies had to go into round after round of layoffs. I can’t imagine the atmosphere inside a startup which is announcing layoffs while its remaining employees are becoming aware that the shares they were thinking of selling during a further round of financing are now worthless.

2 – Downturns

Downturns happen when a startup raises money at a lower valuation than previously. This is supposed to be quite rare as it dilutes former investors (and as they have to announce to their own investors that they made a mistake by overvaluing a company). Even rarer are the cases where startups communicate on this topic.

The most striking example is certainly Indigo, which went from $3.5B to $200M in valuation.

3 – CEOs stepping down and brutal strategic moves

Due to this very public nature, removing a CEO can be a last resort option for a startup (mainly for its investors). The goal is often to demonstrate the startup’s commitment to switching to a new strategy (usually related to profitability). In many cases, it also goes alongside a downturn (where current investors commit some money) in order to attract new funds and follows one or multiple rounds of layoffs that have failed to put the company on track.

Many alternative proteins have recently announced such moves:

- Perfect Day, which had its two co-founders step back, is raising a small amount of money and changing course to focus only on B2B: installing an interim CEO is quite a brutal move and a show of distrust towards the founders from investors.

- Impossible Foods changed CEO two months ago ahead of what it called a “decisive year” (and after layoffs)

- Miyoko’s (a plant-based cheese startup) CEO and founder was removed, which created a long controversy.

4 – Disappointing exits

If the above steps are revealed to be inefficient, selling the startup remains the only option to save face, first for investors and secondarily for founders. For employees, it will be a bad experience (forget about your precious shares; they will get extremely diluted and then acquired for pennies).

In a last-minute effort to avoid bankruptcy, timing is key, and there needs to be more time to negotiate the deal, which often lands on a disappointing valuation.

In recent months, the list is quite long, but here are some delivery examples:

- Boxed, a wholesale grocery delivery startup, was acquired after filing for bankruptcy for much less than the $400M acquisition offer it rejected a few years ago (that hurts) and the $320M it raised.

- Blueapron, a meal kit company once valued billions, was acquired for $103M.

- Quick-commerce startups, ranging from leaders such as Gorillas or local players such as Cajoo or Kavall, were acquired for less than they raised in cash.

5 – Bankruptcies

When all other possibilities have been exhausted, it’s time to declare bankruptcy and eventually shut down the company. This has at least one advantage: we get more information. Indeed, investors, founders, and employees often publicly settle scores.

In past months, it affected all categories:

- Vertical Farms with Infarm: this article is a great read to understand how everything can go wrong inside and around a startup which had raised $500M

- Plant-based products: the list would be very long here, but the best example may be Nowadays, a startup that was praised by commentators. It had fewer ingredients than others but was more expensive—not the best situation in an inflationary market.

Some learnings

First, the following pattern is quite consistent: layoff(s), then a hidden downturn quickly followed or associated with a CEO removal and a strategy change, and a failed exit or bankruptcy.

Secondly, there are some striking similarities between these failures, which we can group into categories:

- The “blind failure“: when a previously highly regarded startup had raised millions for something an obviously unscalable technology or no viable market. This happens repeatedly, and I can only wonder about the seriousness of the due diligence process made by otherwise reputable investors.

- The “awful failure“: when startups fail due to fraud (which often consists of lying about the number of clients or the tech).

But most stories end with what we call a “good failure“: a startup that would have succeeded without an adverse event. Often it went too fast, invested in preparing growth that did not come due to a change in market conditions or bad luck. Here failure is only part of the “startup game”. At then end of the day, we don’t want cautious startups.