I don’t know if you have noticed, but currently, there is a wave of deals around chocolate and coffee alternatives. Indeed, in the past months, at least half a dozen startups raised money on this topic. It doesn’t come from anywhere. For cocoa (but that would be the same thing for coffee and other plants) can at least point to three factors:

1- Prices have doubled due to bad weather conditions and increased global demand. Some companies, such as Hershey, have already said this would affect their product prices.

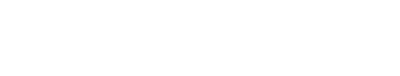

2- Environmental and social concerns: these plants are worse than most animal products in terms of emissions and deforestation. They also have damaging societal impacts. For instance, cocoa is often linked to slavery.

3 – Climate change also affects yields, notably extreme weather conditions like droughts.

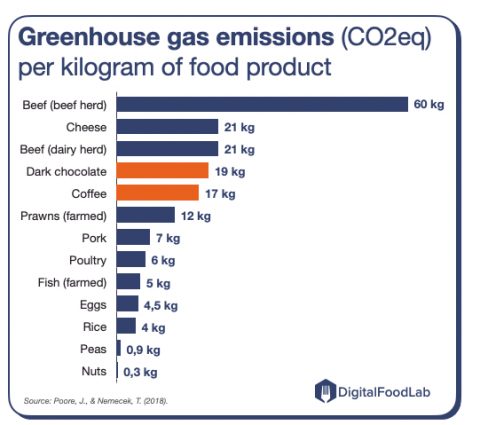

All the above create a need for innovation for alternatives beyond animal proteins. The “easiest path” would be to go for plant-based alternatives. That’s notably the case for coffee and chocolate with startups such as Atomo, WWNW, and Planet A (which just raised $15.4M). Here, we are talking about real substitutes looking to create the same taste, mouthfeel and overall experience as the real stuff, not alternatives that can’t cheat anyone (such as chicory for coffee). Recently, I have had the opportunity to taste some of the mentioned alternatives, and they are really impressive, at least for a non-expert like me.

Beyond, we observe a growing appetite for a small but exciting ecosystem: cultured plants. As shown in the mapping below, these companies are trying to create alternatives to coffee, chocolate, and a wide range of plants, such as vanilla and citrus.

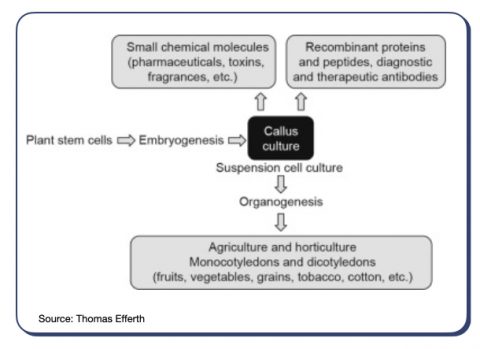

On paper, it looks simple. As shown in the graph below and this research paper, or in this document from VTT, a research centre in Finland, the process is quite similar to cellular agriculture for animal proteins, and the range of potential products is huge.

While investments in cellular agriculture declined by almost 80% last year, this growing appetite for cultivated plant cells may appear contradictory. On the contrary, I see the application of the technology to plants as a response to the two main challenges cellular agriculture faces: price and scale. With plants, the goal is much less to produce proteins at scale but rather to create fragrance. There, volumes are tiny, while prices are high.

There are other benefits, too. First, when it comes to flavouring, consumers may be less reluctant to use cellular agriculture than animal proteins (as it is often already an industry with a high level of hidden chemistry). Second, it may help companies gain resilience: many fragrance compounds come from locations associated with geopolitical risks. Replacing them with a new tech-based source could bring more stability to their supply chains. Obviously, the reverse is true; countries and communities depending on these cash crops could lose their only source of income.

In a word, you can expect to hear much more about plant-based alternatives and “cultivated plants” for ingredients as common as coffee and chocolate, fragrances and other valuable compounds with health benefits. This is definitely a topic that ingredient companies, as well as CPG players, should put at the top of their watch list.